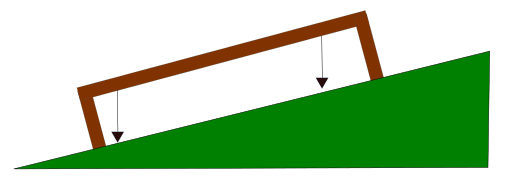

image for illustration: ‘Chorobates – An ancient roman device for measuring slopes’ by Yoni Toker, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

An ambitious project of restoration necessitated an equally ambitious shoring up of infrastructure, reports Open Culture.

Open Culture writes:

We tend to think of the Roman Empire as having fallen around 476 AD, but had things gone a little differently, it could have come to its end much earlier — before it technically began, in fact. In the year 44 BC, for instance, the assassination of Julius Caesar and the civil wars raging across its territories made it seem as if the foundering Roman Republic was about to go down and take Roman civilization with it. It fell to one man to ensure that civilization’s continuity: ‘His name was Octavian, and he was Caesar’s adopted son,’ says science reporter Carolyn Beans in the new Coded Chambers video above. ‘At first, no one expected much from him,’ but when he took control, he set about rebuilding the empire ‘city by city’ before it had officially been declared one.

This ambitious project of restoration necessitated an equally ambitious shoring up of infrastructure, no single example of which more clearly represents Roman engineering prowess than the empire’s aqueducts.

Using as an example the system that fed the city of Nemausus, or modern-day Nîmes, Beans explains all that went into their construction over great lengths of challenging terrain — no stage of which, of course, benefited from modern construction techniques — with the help of University of Texas at Austin classical archaeology professor Rabun Taylor. The most basic task for Rome’s engineers was to determine the proper slope of the aqueduct’s channels: too steep, and the flowing water could cause damage; too flat, and it could stop before reaching its destination.

Surveying the prospective aqueduct’s route involved such ancient tools as the dioptra (used to establish direction and distance over long stretches of land), the groma (for straight lines and right angles between checkpoints), and the chorobates (to check if a surface was level). Then construction could begin on a network of underground tunnels called cuniculi. Where digging them proved unfeasible, up went arcades, some of which — like the Pont du Gard in southern France, seen in the video — still stand today. They do so thanks in large part to their limestone bricks having been arranged into arches, whose geometry directs tension in a way that allows the stone to support itself, with no masonry required. When water began running through an aqueduct and into the city, it would then be distributed to the gardens, fountains, thermae, and elsewhere — through conduit pipes that happened to be made of lead, but then, even the most brilliant Roman engineers couldn’t foresee every problem.

Read more….